I have to say, I think I was very lucky to be in the right place at the right time. But beyond that, it took enormous effort and an exceptional team to make a film that hopefully captures something of Alexei’s spirit and the importance of his fight for all of us.

At the beginning of 2020, Karl von Habsburg approached me and said “Do you know this Alexei Navalny? I might have a lead about the people who wanted to poison him.” As soon as he said these words, I knew how I would be spending my next year. He introduced me to Navalny’s close friend and ally, the renowned Bulgarian journalist Christo Grozev, whose specialty among other things was uncovering Russian poisonings. And a few weeks later, we were traveling to the Black Forest, which is where I met Alexei.

We presented our plans to him about the documentary, and he got it immediately – if our story was to trace the course of the criminal case, then we would have to start straight away. In the next three and a half months, the film developed into an intimate portrait of a person, his family, his allies and the victims willing to stand up for their convictions – for values such as freedom of speech, democracy, human rights and their desire to live in a country not governed by corruption. The whole filming took place in secret, and it wasn’t until the end of December 2020, before Alexei returned to Russia, that we were able to act openly and develop a strategy.

The film is shaped by the tussle between a media pro and me, as the director of an independent production. I knew that this film had all the right ingredients for a thriller, but also that I was capturing an important moment in history. NAVALNY combines intimate interviews, social media, Russian propaganda and dramatic camera movements. Stylistically, we’re questioning the traditional relationship between the director and his interview subject, making a film instead in which the director, interviewee and audience are all actively involved.

He has this energy that’s often ascribed to gifted politicians. Navalny makes you feel like you’re the most important person in the room. All of a sudden, I thought, “This man could be president.” Apart from that, he’s also very funny although he could flare up at times and with his colleagues, he was tough. When it comes to the media though, he’s a real genius – the way he could influence the news cycle to suit his aims and use the internet for his own purposes. For me, he’s the conscience of the Russian opposition. Even from prison, he’s their leader, and he can even be described as their moral center. He says, that when he saw Putin for the first time at a public appearance, he had the familiar feeling that he was looking into someone’s eyes knowing all the time that they were lying. And that was what made him act.

Although I don’t approve of everything he’s done, I can understand his political calculation – as he needed a broad coalition to be able to overturn Putin. In the film, Alexei says, “If I want to fight Putin and become political leader of a country, then I can’t simply ignore a huge part of that state. In a normal political system, there’s no way I’d be in the same party as these people. But we’re creating a broad alliance to fight the regime and to create a situation where everyone can take part in the elections.”

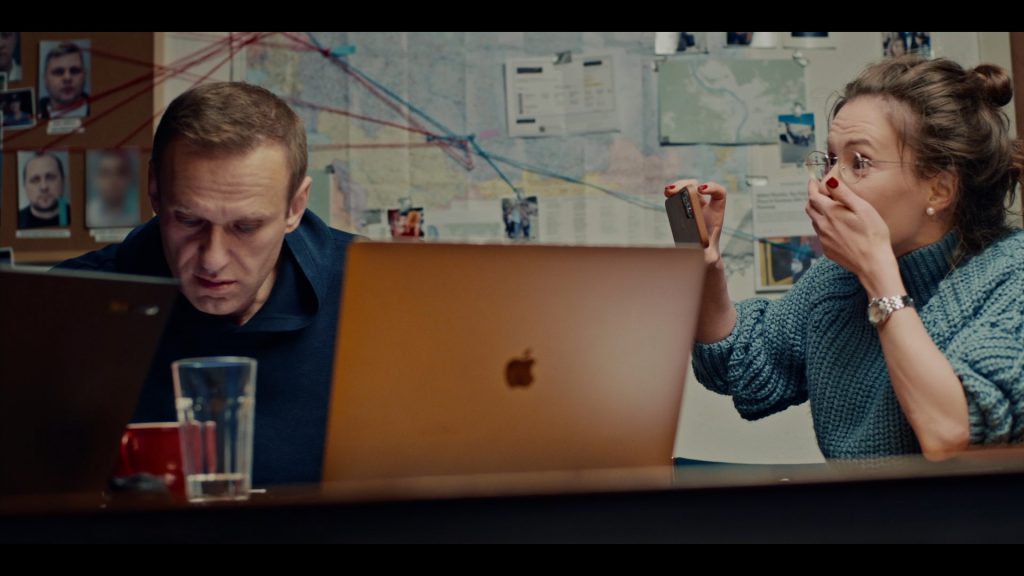

When Alexei decided to call the men from the Russian Federal Security Service, the FSB, whose job it was to murder him. The night before, I asked Christo what he was expecting from this call, and he said, “It might make a nice scene for the film, but no-one’s going to give anything away. They’re all spies. They won’t say anything on the phone, there are rules for that.”

When it came to it, everyone he called hung up, just as we expected. I don’t speak a single word of Russian, but when Alexei called the military chemist Konstantin Kudryavtsef, I could understand what was going on. Navalny talked to him for 45, 50 minutes and he gave him the whole story. It was one of the most exceptional moments during filming.

One scene that really means a lot to me is where Alexei is walking through the snow. It’s a strong visual metaphor for a man who’s made his decision, is resolutely following his path and won’t let himself be dissuaded from it by anything.

I want to remind the audience that, if people don’t pay attention and just don’t care any more, then bad people win. Whether that’s authoritarian rulers in Brazil, Hungary, Turkey, Russia, China or the USA. Alexei wants to remind us that we cannot not act. That’s what people should focus on when thinking about him.

It was always clear to me that we were making a film about a man that had his own agenda. It’s the metanarrative that runs through the film. We have film A, about the man, his family, the investigation into the attack and his return to his home country, but there’s also film B, about a director striving to be objective while making a film about a politician. We show Navalny, I think, as a politician that we should continue to support, despite his faults, as his mission is immensely important. It’s our moral duty. And his courage should inspire the whole world.