In 2014, Mills had a child with Miranda July. It was, for him, an instantly disorienting, then slowly revealing, transition, not unlike what Johnny experiences in C’mon C’mon, if not nearly as out of the blue. Mills knew he wanted to explore what was happening. But, in his typical way, his screenplay became a kind of cinematic auto-fiction: a candid, highly subjective self- accounting, one that takes place inside an imagined family and pulls from myriad influences around him—the movies, music, books, and people that inspire him, as well as the rhythms and textures of the culture we all live in right now.

“With C’mon C’mon, I wanted to play with opposing scales,” Mills says. “On the one hand the film is about the smallest of moments: giving a kid a bath, talking before bedtime. On the other, you’re traveling to big cities, hearing young people think out loud about their futures and the world’s future, so the intimate story is happening in the context of a far larger one. I often feel this same spectrum with my kid: our time together is so private, yet the biggest concerns of life are all there.”

Mills is fascinated by the pervasive links between the small, individual worlds we each inhabit and the big one we live in together. Writing about the most personal fears and intimate triumphs of parenting became entwined, for him, with documenting some of the vast complexity of young lives in the early twenty-first century America, as kids inherit the perils of our times from bewildered adults.

He hit on the road movie as an ideal structure for that mix. He could not help but think of a film he loves, Wim Wenders’ Alice in the Cities—the story of a German journalist who travels with a young girl after her mother doesn’t show up. “Early on, I thought of C’mon C’mon as almost a blues riff on Alice in the Cities,” says Mills, “because, like Wenders, I wanted to explore a child character as a creature with volition, concerns, and wants, and fears that are as valid as any adult’s.”

But the story soon took off in its own direction. Mills created the lead character of Johnny as a contemporary radio journalist—a man drawn to the art of listening, yet perhaps a bit out of time. Johnny’s occupation draws from Mills’ life—in 2014, he made a documentary for MoMA, A Mind Forever Voyaging Through Strange Seas Alone, in which Silicon Valley kids imagine what the future might look like technologically, environmentally, and personally. Johnny is making a similar radio series, traveling to different cities to talk to a broad spectrum of kids about their joys, fears, and hopes.

Johnny is clearly not a precise counterpart of Mills. He is insular, even willfully alone, estranged from his sister and split from longtime girlfriend. He doesn’t anticipate how caring for Jesse will shake up his life. But what Mills homes in on is how liberating it becomes for Johnny, how it lays bare certain things he had not seen about himself, and how healing it is to take care of this kid.

Mills chose to write about an uncle in part because it was a way to plunge an unsuspecting character literally overnight into the full-on intensity of parenting. “Johnny has to learn everything a parent learns but very, very fast,” he says. “As a father, I’ve found that you feel you’re constantly a novice, trying to keep up as things shift, and this was a way of recreating that confusion, that always being not quite ready for what’s happening. Of course, you don’t have to be a biological parent to experience that. You can be an uncle, an aunt, a teacher, or caretaker.”

Mills felt a pull to render a child’s closeness to an adult with all the complications, mixed motives, and bursts of wonder found in any major relationship—on both sides. “There’s a constantly interesting back-and-forth you have with a child that we rarely talk about,” Mills says. “It can be as light as playing but then it can be as deep as any adult relationship you’ve ever had.”

A constant theme in Mills’ work is memory, the things that persist, the things we miss, and that particular sinking fear that those elusive bolts of bliss can’t help but slip through our fingers. In C’mon C’mon, Johnny has the urgent sense that he needs to somehow capture what is happening with Jesse, even if all he has is their voices to do it.

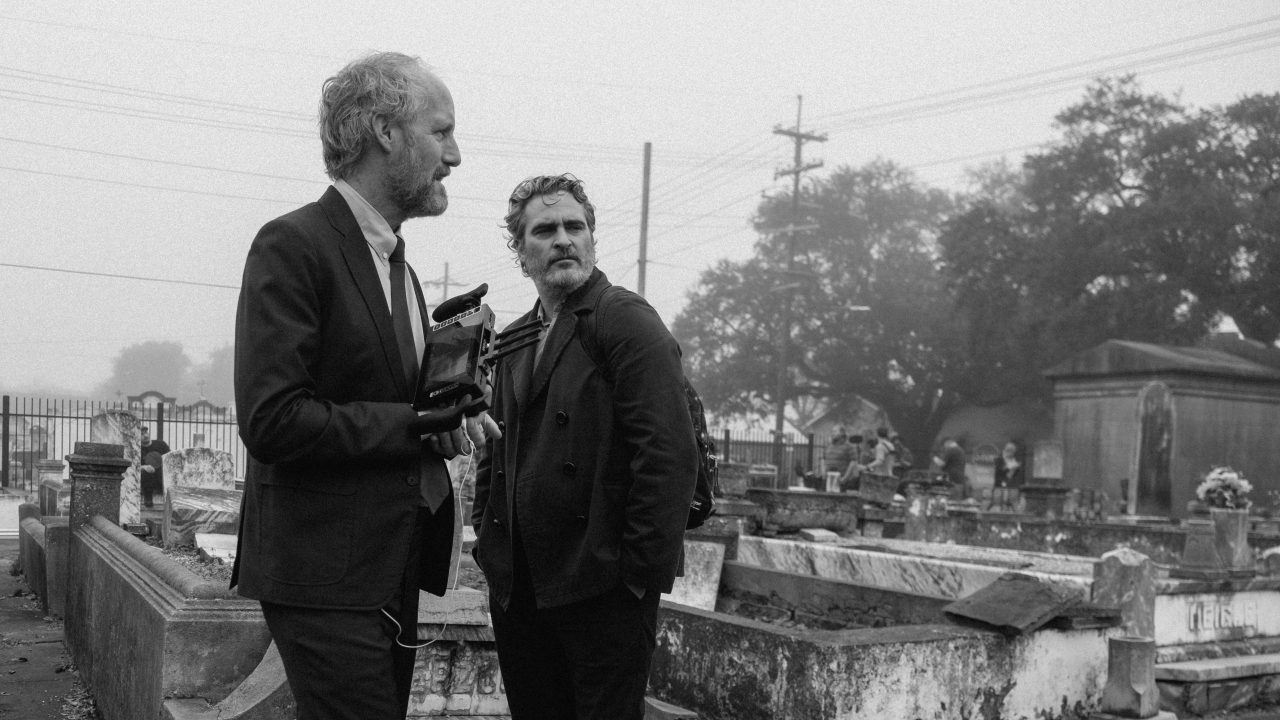

As he wrote, Mills realized that ultimately the script would be reliant on two actors taking the roles to places he couldn’t foresee. That’s exactly what happened when Joaquin Phoenix and Woody Norman entered the picture. Suddenly, Mills was capturing the thrillingly immediate unfolding of a fellowship right there in the rooms and streets where they were shooting.

“What started as me trying to document and think about my life with my kid became equally a portrait of the relationship that developed between Joaquin and Woody,” Mills says. “I really tried to embrace that and let the camera capture that. And that’s when I get most excited as a filmmaker: when things feel that alive, unpredictable, surprising.”